Cartoons for Propaganda

Article by Prof. Ricardo T. Jose

Reprinted from Kasaysayan: The Story of the Filipino People, Cartoons for Propaganda p. 258-259

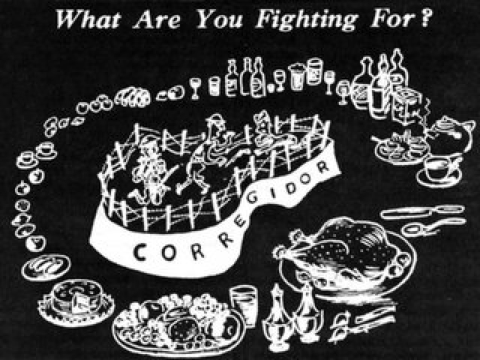

Dropped by Japanese war planes in the island of Corregidor during the intense bombing of the island fortress, this leaflet was meant to convey the message to the Filipino-American soldiers the futility of fighting, and to surrender, as their resistance was hopeless. The Filipino soldiers at this time were already demoralized by the lack of food and constant bombings by the Japanese, and the cartoons showing plenty of food waiting for them outside Corregidor was meant to take advantage of this weakness.

Cartoons and comics have been a part of the Filipino world since the 19th century, perhaps even earlier. They have been used to provide entertainment, humor, and satire as well as to provoke comment and action. During the Japanese Occupation, both the Japanese and anti-Japanese forces knew that cartoons could be put to good use – as propaganda tools, to bolster morale, and to push fencesitters off their neutral perch.

The Japanese used cartoons and comics widely in the publications they controlled. The Tribune initially carried some prewar American comic strips (Mutt and Jeff, Tarzan, Donald Duck) in the first month of occupation in Manila, to allow for some semblance of continuity and normalcy in the new order, but these were quickly stopped. Some of these, however, ridiculed the U.S. military, thus fitting in with Japanese propaganda aims. Some of the prewar Civilian Emergency Administration’s illustrations were also initially used to drum up the importance of producing food.

As the occupation wore on, however, the Japanese brought in Japanese artists and cartoonists to show Filipinos that Japan also had cultural greats. In January 1943, the Tribune introduced a new comic strip, “The Boy ‘Filipino’,” drawn by a visiting Japanese artist, Keizo Shimada. Perhaps because the humor was different from Filipino humor, or because Shimada’s Philippine stint ended, the strip lasted for just over two weeks.

Filipino comic strip and editorial cartoon writers were made to work for the Japanese-controlled publications. Liborio Gatbonton, well-known as Gat, was made to draw caricatures of Filipino political leaders under the Japanese. Tony Velasquez, creator of the comic character Kenkoy, was made to do Kalibapi F mily, a new strip following the inauguration of the Laurel Republic. The messages in Kalibapi Family, however, were more pro-Republic than pro-Japanese, emphasizing unity and civic consciousness among Filipinos while discouraging buy-and-sell and get-rich quick schemes.

Other Japanese-controlled publications also made use of political cartoons and comics. Shin Seiki, the lavish photographic monthly styled after Life magazine, utilized some editorial cartoons by Filipino and Japanese artists. At least one comic book, Si Pamboy at si Osang, was published, to discourage Filipinos from believing rumors that the Americans would return, and enjoin them to cooperate in building a New Philippines. Although the work of Filipino and Japanese artists was given much publicity, and the names and techniques of Filipino artists were well-known, the comics and cartoons, as with other forms of Japanese propaganda, fell flat.

More powerful – because they reflected the people’s sentiments – were underground cartoons which criticized the Japanese and those whom Filipino perceived as their collaborators. Some of the guerrilla cartoonists were not well-known, or were not professionals, but their works spoke volumes and echoed the Filipino mind. For lack of paper and printing facilities, many of these cartoons were stenciled and mimeographed; others came out only once and were circulated until they fell apart.

In Negros, an underground newspaper called The Voice of Freedom, together with the Visayan counterpart, Tingug sang kalwasan, sported illustrations – often individually hand-colored – by Jose Montebon. In Manila, Conrado G. Agustin did painfully accurate descriptions of the symbolism of Japanese occupation – and” was arrested and tortured for it.

In the hills just outside Manila, Esmeraldo Z. Izon, famed political cartoonist of the Philippines Free Press, sketched and poked fun at the Japanese, satirizing slogans by the Japanese and Laurel. Instead of “New Order in Asia,” Izon drew a cartoon of two Japanese, one urinating and the other defecating at the Escolta, and called this the “New Odor in East Asia.” Playing on Laurel’s foodraising campaign slogan, “Magtanim Upang Mabuhay” (Plant to Live) Izon drew a cartoon showing a fat Japanese hauling away a cart of food while a Filipino salivated, with the title “Magtanim Upang Mabuhay Ang Hapon!” (Plant for the Japanese to Live). Izon, who had been forced to work with the Manila Shimbun-sha, escaped in 1944 and joined President Quezon’s Own Guerrillas, with whom he illustrated the guerrilla newspaper The Liberator.

Other guerrilla groups throughout the Philippines put out their own underground newspapers and leaflets, spiced up with cartoons attacking and poking fun at the Japanese. These proved popular with Filipinos and kept the spirit of liberty alive, although to be caught with them by the Japanese meant torture or death.

Like the Japanese, the Americans realized the impact comics could have on the Filipinos, and in Australia a special comic book – The Nightmares of Lieutenant Ichi, or Juan Posong Gives Ichi the Midnight jitters – was printed and sent to the Philippines by submarine. The comic book showed how Juan Posong, a typical naughty Filipino lad, used every trick in the book to torment Lieutenant lchi, a not too-intelligent Japanese officer. In the end, Juan Posong’s tricks and games prove too much for Lieutenant Ichi, and he hails a passing calesa: “MacArthur Come! Nippon Gol” he says, in a pun on the word Nippongo, the Japanese language. To rub it in further, he says “Nippon-Go to Tokyo!”

Some Filipino artists, like Fernando Amorsolo, sketched their impressions of the Occupation, which would see public exhibition only after the war. Others, as soon as the war ended, documented what they saw and continued the satire against the Japanese. Gat, for example, quickly sketched pictures which reflected the common sights of the occupation – in a humorous style – and published them in a book called Jappy Days. Since film was scarce and controlled by the Japanese, this collection of cartoons and vignettes is one of the few graphic and humorous records of the Occupation.

After all, although the Occupation meant a lot of suffering, many Filipinos were able to smile their way through it.

ARCHIVE: